Kim O'Connell

|

I wrote this poem for Thou Art: The Beauty of Identity, a beautiful poetry chapbook produced by Studio Pause in Arlington, Virginia.

A Mother A mother, a maker of laundry and burned toast, late holiday cards and bad haircuts, secret wishes under glow-in-the-dark stars. A mother, a breaker of cups and small toys, promises and soft hearts-- theirs, because she is not all they want her to be, and hers, for the same reason. In the city, the urban glow makes for a kind of endless dusk. The night in Shenandoah is completely different. One night while I'm staying there, I walk to an amphitheater about a half-mile from my room to hear a park ranger talk about animal calls. During the day, this walk is negligible, a leg-stretcher. Nightfall changes everything. Without streetlamps, I am reminded of what true darkness is. I switch on my flashlight.

The funny thing about flashlights is how they pull your focus to the tube of light ahead of you and nothing else, so you ironically see less. With my light on, I feel intrusive and conspicuous, seen rather than seeing. I decide to turn off the flashlight for the walk back to my room. I let the darkness envelop me, covering my body in a way that feels charged, almost erotic. After a while my eyes adjust and I see shadows cast by the gibbous moon. The stars look like sugar spilled across my walnut dining table back home, grain piling on grain. All my other senses are heightened too. I hear the call of a coyote in the distance and the breeze whirling through the high canopy of trees--trees I can’t really see, but whose immensity I sense all around me. The ground is hard beneath me, holding me up. “We don’t sing of the night anymore,” the environmental writer Thomas Becknell once wrote. I find that I want to sing. I was pleased to moderate a panel at the annual AWP Writing Conference in Washington, D.C., this past week, focusing on being an artist-in-residence in the national parks. Here is the text of a corresponding handout from the panel with information on being a national park A-I-R:

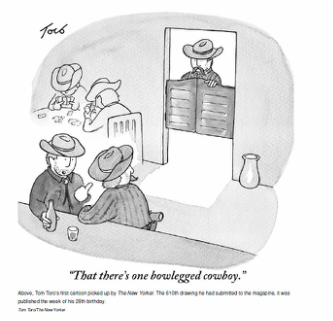

Dozens of sites in the National Park System have artist-in-residence programs, and most support writers. Some parks might have open calls for all kinds of artists to apply, whereas others might put out calls for certain types of artists, so that writers might have to wait until applications for their specific discipline are requested. Most A-I-R programs are run by the National Park Service, often with support from private donors and trusts, but some residencies are administered by educational institutions or art foundations in partnership with the park. General information/structure: Park A-I-R programs vary widely, but generally the resident artist will be provided lodging (doubling as work space) for a period of 2 to 4 weeks. The artist is generally expected to provide food, transportation, and any necessary supplies, although some parks might offer a stipend or per-diem to help cover food. Lodging can range from hotel-like rooms or apartments to private or rustic cabins; expect accommodations to be basic but sufficient. During the residency, some kind of public engagement is usually required of the artist, e.g. a workshop, reading, a lecture during a hike, etc. A-I-R programs also often require that artists donate some work of art to the park after their residency. For writers, this may mean allowing their writing to enter the public domain, since the park is governed by a federal agency. However, writers would generally be free to publish their work elsewhere and to adapt the work into something fundamentally new (and thus copyrightable), as with any public domain work. Such requirements would be outlined in a contract that artists would sign prior to the residency. Application requirements: Although the process will vary from park to park, generally A-I-R applications will require the following information: * An artist’s statement about your particular writing focus, your background and accomplishments * Project proposal to be undertaken in conjunction with the residency * Description of public program (workshop, reading, etc.) * Resume or curriculum vitae * Writing sample(s) * Contact information for references who know your work and can attest to your ability to work independently in this kind of residency Web sites: ** Be sure to check individual national park web sites for specific information.** National Park Service A-I-R web site National Park Arts Foundation Alliance of Artists Communities Artist-in-Residence Field Notes (for former/prospective A-I-Rs)  Joe McMahon remembered the first car he ever bought like some people remember their first kiss. It was a 1934 Ford Coupe, all-black with yellow wheels and white sidewall tires, along with a rumble seat--an ingenious extra bench seat that folded up from the back of the car. "It was beautiful," McMahon told me in an interview last year, one of the last ones he gave before his death in September 2015, at the age of 90. "I bought it for $250 in 1943 from a friend, because he was going into the service. I wish I had that car today. Six months later, I had to sell it when it was my time to go into the service." McMahon was born on December 30, 1924, in Columbus, Ohio. His early life was marked by turmoil. His mother died when he was four, and his father was a traveling salesman selling razor blades in south Texas, so McMahon and his sister were cared for by his grandparents and aunts. "In those days the choice was relatives or an orphanage," McMahon said. "My dad would send up money for them to take care of us." To pass the time, McMahon studied cars. The first car he ever noticed was his father's Franklin roadster. In 1902, the Franklin Automobile Company had developed a line of luxury cars with air-cooled engines (as opposed to standard combustion engines dependent on liquid coolant), the details of which were fascinating to the young boy. By the time he was 12, McMahon's father had remarried and brought his children down to San Antonio to live permanently. "From that point on, we would drive down the road together and I could tell him the name of every car that passed us," he recalled. "They were all different looking, not like they are today. Cars are all cookie-cutter today." As soon as he turned 16, McMahon was itching to get behind the wheel. He first learned to drive in his stepmother's 1931 Chrysler Coupe. Only a couple years later, he was able to purchase his own, the 1934 Ford, but he could only enjoy it for a few months before the war came calling. He was 18 in 1943 and about to be drafted. He didn't want the infantry, so he enlisted in the Army Air Corps. “They gave me a physical and threw me in there,” he recalled. With the war raging across the globe, McMahon was fast-tracked past basic training and sent to the Sheppard Field in Wichita Falls, Texas, where they put him up in the air as quickly as possible. He had never been within walking distance of an airplane before. "Instead of having 10 weeks to prepare, we had 4 weeks,” he said. “They needed recruits. I was basically cussed at for 45-minute periods endlessly with my trainer in these two-seated open airplanes." From there, McMahon underwent additional training at Ellington Field in Houston and attended navigation school at the San Marcos, Texas, Army Airfield, and gunnery school in Laredo near the Rio Grande. From there, it was on to Italy, where McMahon flew 30 B-24 missions with the 15th Air Force, bombing military targets in Germany, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. His first mission was to a synthetic oil refinery up in Poland, one of several Nazi fuel production centers. "They expected us to lose half the planes just from running out of gas,” he said. “But we had to knock that synthetic oil plant out of there." He had several close calls and his planes were occasionally hit with anti-aircraft flak. One time, he was on an airdrop supply mission for prisoners of war in the Alps, and his pilot literally scraped the plane's tail on the top of a mountain as they were flying over it. "They were not going to shoot me down," he said emphatically, his voice raising. "And if they did, I was just going to walk from Yugoslavia or wherever back to the base." He befriended a young boy at a British airfield on the coast of Yugoslavia. "He wanted one of the wings off my uniform, so I gave it to him," McMahon said. The boy gave him a homemade star in return, which McMahon still had 70 years later. McMahon had already been sent home from Europe after 27 months of service when he got the news the war had ended in Japan. After the war, McMahon earned a degree in business administration from the University of Texas at Austin, and went into the traveling sales business with his father, now focusing on selling pencils in bulk. He first marriage produced two children (one now dead, the other still living in Houston), but the marriage lasted only 11 years. After his divorce, he met a woman named Sammie at a country music bar. "She was so sweet and pretty and loved to dance and threw great parties," McMahon recalled. "We just made a good fit. I was married to her for 35 years." Sammie died in 2000. It was during this marriage that McMahon rekindled his love of cars. He first purchased a 1952 Mercedes black convertible, which McMahon had redone with cream paint and red-leather upholstery. Not long after that, McMahon bought a 1955 lemon-yellow Thunderbird, beginning a lifelong passion for TBirds. He soon added a 1962 Thunderbird Roadster to his collection. He and Sammie lived their lives in those cars, going on road trips, running errands, working on them in the garage. To find others who shared his passion, McMahon eventually founded the South Texas Vintage Thunderbird Club, which still meets regularly today. The club honored McMahon's World War II service in a special ceremony. A couple years ago, McMahon also joined several other World War II veterans on an "honor flight" from Texas to Washington, D.C., where they visited Arlington National Cemetery and the World War II Memorial, a moving trip that allowed McMahon to pay tribute to his fallen comrades. Over the years, McMahon sold his older model TBirds at a handsome profit, but he kept two--a 2002 model with 11,000 miles on it, and a light tan '05 50th-anniversary edition Thunderbird with only 6,000 miles on it. McMahon--decorated World War II veteran, traveling salesman, and lifelong car enthusiast--was still taking his beloved TBirds out for a spin until his very last days.  An arrangement at the funeral of Mr. Nguyen Ngoc Bich, March 12, 2016. An arrangement at the funeral of Mr. Nguyen Ngoc Bich, March 12, 2016. It’s an odd feeling, being a stranger to your own heritage, but that’s a feeling I’ve had most of my life. I am the daughter of an American father and a Vietnamese mother. My parents met during the war, when my father was a U.S. Army captain stationed on the base at Okinawa, Japan, where my mother had been hired to teach Vietnamese to U.S. soldiers. After a brief and passionate courtship, they married on Okinawa and moved back to the States. Unfortunately, they divorced in 1977, and my newly single father was awarded custody of my young brother and me. Thus, I grew up fully immersed in American customs, eating burgers and hot dogs, going to public school, and hanging out at the mall. It didn’t help that I was tall and white-skinned, with medium-brown hair, wholly resembling my Irish-American father. I didn’t look like my Vietnamese mother at all. Even in those times when I was with my mother, when we would cook spring rolls together or visit the Vietnamese shops at Eden Center in Falls Church, Virginia, I never felt very Vietnamese. As a child, that didn’t matter that much to me. But as I got older, I began to desire a stronger connection to my Vietnamese heritage. Without that connection, it felt like I was always standing on one leg. I sought to learn more about Vietnam and the experiences of people in the Vietnamese community. When I was in graduate school at Goucher College, studying historic preservation, I began to research and write about the section of Arlington, Virginia, that had been settled by Vietnamese immigrants and refugees after the fall of Saigon and was eventually known informally as “Little Saigon.” It didn’t take long for this work to lead me to meet Mr. Nguyen Ngoc Bich, whom I interviewed for my graduate school paper, as well as several other members of the local Vietnamese community. We sat in Mr. Bich’s basement, surrounded by his voluminous books, photos, and papers, as he told me about his many experiences in Arlington, working for the School Board and other entities in several capacities that served the local Vietnamese population. He was an author, translator, educator, community spokesperson, lobbyist, and so much more. But most of all, I remember being impressed by his warmth, intelligence, and generosity. Then, in 2004, Mr. Bich and I came together again to film a segment about Arlington’s Little Saigon for a PBS (WETA) documentary called “Arlington: Heroes, History, and Hamburgers.” Again, Mr. Bich was a sensitive, authoritative figure who offered meaningful insights about this essential time in Virginia history. His warm smile was, to me, the highlight of the segment. When I was with him, he made me feel accepted as a member of this community too. He gave me permission to stand on both legs. Some time passed, but with the 40th anniversary of the fall of Saigon in 2015, interest in commemorating Arlington’s unique Vietnamese heritage--particularly recognizing Little Saigon as the first place of refuge for Vietnamese in Virginia after the war--was growing within county government. I was honored to work with representatives from the community as well as Arlington’s historic preservation, cultural affairs, and public art departments, along with gifted students from Virginia Tech, to recognize the beginning of Vietnamese resettlement in this area. It was essential that Mr. Bich be a part of this burgeoning effort. It was a real pleasure to introduce him at a commemorative event that recognized this history through the collection of oral histories and an audio tour of the former Little Saigon, as well as a public art installation. (Mr. Bich himself recorded an oral history interview that has now been transcribed and is available to researchers at the Arlington Public Library’s Center for Local History.) This year, we were about to start work together yet again on a booklet about Arlington’s Vietnamese heritage, funded with a grant from the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Mr. Bich was to be an expert scholar on this project, and I was so pleased when he attended the kick-off meeting for this effort in January 2016. It was a shock to receive the news that Mr. Bich had passed away only about a month later. Mr. Bich’s passing is a huge loss to the Vietnamese community, as well as to the community of educators, students, historians, activists, and scholars that he has influenced both here in America as well as in Vietnam and other parts of Southeast Asia. It is also a huge loss to me personally. Mr. Bich was a generous mentor and friend who showed me what it means to be Vietnamese. Just as he helped so many people to find and hold onto their own history, Mr. Bich helped do the same for me.  Illustration by Victo Ngai for The Washington Post. Illustration by Victo Ngai for The Washington Post. When you have a child, you immediately make all the decisions for this other human being, deciding what they eat, what they wear, where they sleep, where they go, who they will play with, and so on. You are utterly, irrevocably in charge. If you happen to also be a writer, this gives you a heady power. Suddenly, this is not just a child but a font of story ideas! The Internet is littered with blogs, articles, lists, status updates, tweets, and more about what curious, adorable, touching, or infuriating things our kids are doing. I bet, in most of those cases, the parents didn't ask the kids for permission to write about them. Those rambunctious toddlers didn't sign any kind of use agreements or contracts. After all, this is mommy's life we're talking about, right? These are our children! They belong to us, so therefore we can feel free to write about them as we wish. I once thought this way too. When my son was three years old, he developed a social anxiety disorder called selective mutism (SM), wherein a child who can otherwise speak normally becomes mute in certain situations, such as school or daycare. In our case, for a while our son stopped speaking everywhere, including at home with my husband and me, and it was a very frightening and stressful time. To process what we were going through, I started a blog, now dormant, which served as both an outlet for our experiences as well as a way to connect with other families facing this same confounding condition. When I started writing, I used my son's real name and wrote about very personal things, like embarrassing play dates where he refused to cooperate, the many times I lost patience with him, and even his bathroom habits. Later, I published a personal essay about SM on the parenting site Babble, again using my son's real name. It didn't occur to me, then, that this might be an invasion of his privacy, or that if I had told him what I was doing or allowed him any agency at all, he might have objected to my writing about him. Things became clearer to me when my Babble piece was picked up on the front page of Yahoo News. For days, my very personal story went viral, garnering more than 1,000 comments and many shares. Although I received tons of support, I also got slammed by the usual contingent of trolls, as well as others who dismissed me as an overanxious mom making mountains out of molehills. What hurt the most was seeing people make judgments on my son, tossing his name around like a football. I felt like I had given birth to this child and then thrown him to the wolves. It was a hard lesson. As the years passed, the invisible umbilical that ties all mothers and children together began to stretch out. My son became more and more of his own person. I began to realize that, as much as his anxiety disorder was something I was going through and processing, it was his life I was writing about. I recognized, belatedly, that he had a right to privacy. Yes, perhaps I should have felt that way all along. But I'm glad I came to that conclusion even late in the game. I stripped his name from all my previous writings about him, and I confessed to him about all I had written. My son is now 8 years old, a talkative kid who has fully conquered selective mutism. Yet I still feel that our experience and this condition are worth writing about, so this spring I pitched an essay about him to The Washington Post. Before I did so, I asked him how he would feel if I wrote a story about him and his SM. After considering it, he agreed, but said I couldn't use his name or his photo. I totally concurred and gave my story to the Post with these restrictions, which they thankfully abided by. My article was published both in print and online, with a lovely and poignant illustration by Victo Ngai, shown here. When it was published, I asked my son if he wanted to read the story, and he said no. I didn't badger him about this. Perhaps he will tell his own version, in his own way, in the future, and I hope he does. But it's his choice. Whose life is it anyway? It's his, it's mine, and it's ours. I'll keep writing, but I'll do it out in the open.  Isaac Asimov once said that rejection slips are like "lacerations of the soul, if not quite inventions of the devil." I've been thinking about rejection a lot lately, in part because I recently gave a talk on this topic to the wonderful writers of the Capital Christian Writers group. In my talk, I referenced the remarkable tenacity of cartoonist Tom Toro, who submitted 609 cartoons to The New Yorker that were all rejected. Then, finally, his 610th cartoon struck gold, and he achieved his longtime dream of being published in The New Yorker. I've posted his very funny cartoon. I have plenty of my own rejection stories. A few years ago, I wrote a personal essay about my often-strained relationship with my mother, who is Vietnamese. I called it "The Saving Grace of Spring Rolls." I poured my heart into this story, which talked about how making my mother's beloved spring roll recipe brought us together when other things drove us apart. I believed in that story. Over the course of three years, I submitted that story to over a dozen magazines and two writing contests. It originally was about 1,800 words long. When that didn't get me anywhere, I pared it down. When that still didn't work, I reworked it, striving to find its essence. I kept sending it out, and it kept getting rejected. At some point, I took out a piece of paper and wrote "Never give up" on it five times, like this: Never give up Never give up Never give up Never give up Never give up I kept that on my desk. I kept going. I didn't give up. In November 2012, I submitted my essay to Ladies Home Journal, which had a "Story Behind the Recipe" column. By that point, my expectations were tempered. And, in predictable fashion, I heard nothing. The following February, I submitted a shorter version of my essay to the Bethesda Literary Festival writing competition in Maryland. Finally, I caught a break. The essay earned an "honorable mention" in the competition. I was thrilled that this essay that I so believed in had finally earned some validation. Then, one day in July, I had a phone call from an editor at Ladies Home Journal, a full eight months after I had submitted to them. The editor apologized for keeping me waiting and said she wanted to publish my spring roll story. Believe me, that call was so worth the wait. My piece appeared in Ladies Home Journal last May. I've come to realize that rejection is simply the universe's way of telling me that I am brave and strong, and that I am pushing myself into new and possibly uncharted territory. Rejection means that I am gaining ground, not losing it. I've come to view it as my old and helpful friend.  I've always been drawn to cairns, those totemic piles of rock that appear alongside lakes and trails, almost as if by magic. Think about it: Have you ever seen anyone actually build one of these? I'm half-convinced that there are sprites in the woods whose sole purpose is to find a seemingly disparate pile of rocks and bring them into perfect balance. Last summer, our family took a two-week driving tour to Wyoming, spending the largest part of our trip at Yellowstone National Park. On a day trip to the Grand Tetons, just south of Yellowstone, we took a short hike around scenic Colter Bay, in whose blue water the snow-capped Tetons were perfectly reflected. We bounded down to the water's edge and were astonished to see the rocky beach full of cairns, large and small. The cairns were a clear nod to the mountains in the distance, a way of mimicking their towering forms while at once acknowledging that they couldn't possibly be matched. They were lovely and powerful, and I felt perfect peace there. Ten years ago, my husband Eric and I spent a week in Acadia National Park, a province of rugged but accessible peaks jutting out from the Atlantic coast of Maine. There too, the trails and summits are marked by cairns, some of which are known to be more than 100 years old. Yet the cairns invite so much fiddling by visitors in the form of adding and subtracting rocks that the National Park Service has to post signs urging people to leave them alone. I don't think I touched any of the cairns when I was there, but I confess to wanting to. Part of me feels guilty about this cairn fetish, though, as if I should stand up for nature in its unaltered state. But I'm enough of a realist to know that not much of nature is truly unaltered. The same trail that brings me to the cairn was carved out by someone. Park boundaries are limited by the highway (or farm, or ranch, or suburb) on its edge. That might make me sound cynical but truly, I'm not. As a city girl, I want to let it all go, to believe I am a little bit lost and that nature prevails. When I'm out in the woods, I'm used to pretending I don't hear the jet engines overhead or see the footprints of others who have gone before me. And yet I can't ignore a cairn. So it was yesterday. I'd just arrived at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts for an eight-day writing fellowship in southwestern Virginia. After getting settled and actually getting some writing done (I'd expected more daydreaming for my first day), I decided to go exploring. Nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains, the VCCA Fellow's Residence and Studio Barn are surrounded by thick woods. When I checked in, I was told to look for a white- and red-blazed walking trail. This was easy enough to follow, for a while. But with it being winter and the trees barren, the trail was covered with leaf litter and hard to keep track of in places. The deeper I went into the woods, the farther and farther apart the blazes seemed to be. I tried not to feel nervous--after all, I could still hear the cars on a nearby highway, my cell phone still had a signal (see "city girl" reference above), and I knew the whole trail was no more than two miles--but I was a little chagrined that the trail wasn't clearer. Then I walked up a hill and there was this beautiful cairn--a beacon bathed in late-afternoon light, a wayfinder in the woods, a sign telling me that I wasn't lost. It was a reminder, one I get far too rarely in my life, that everything was in balance and I was on the right path. I sent a silent thanks to the unknown soul who built it and kept walking. |

Kim A. O'ConnellThoughts on writing, travel, people, and places. Categories

All

Archives

January 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed