Kim O'Connell

|

I was pleased to moderate a panel at the annual AWP Writing Conference in Washington, D.C., this past week, focusing on being an artist-in-residence in the national parks. Here is the text of a corresponding handout from the panel with information on being a national park A-I-R:

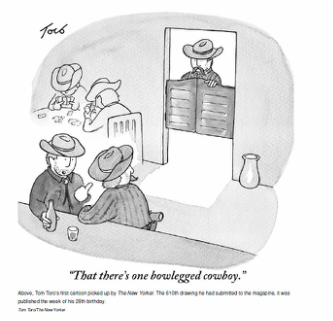

Dozens of sites in the National Park System have artist-in-residence programs, and most support writers. Some parks might have open calls for all kinds of artists to apply, whereas others might put out calls for certain types of artists, so that writers might have to wait until applications for their specific discipline are requested. Most A-I-R programs are run by the National Park Service, often with support from private donors and trusts, but some residencies are administered by educational institutions or art foundations in partnership with the park. General information/structure: Park A-I-R programs vary widely, but generally the resident artist will be provided lodging (doubling as work space) for a period of 2 to 4 weeks. The artist is generally expected to provide food, transportation, and any necessary supplies, although some parks might offer a stipend or per-diem to help cover food. Lodging can range from hotel-like rooms or apartments to private or rustic cabins; expect accommodations to be basic but sufficient. During the residency, some kind of public engagement is usually required of the artist, e.g. a workshop, reading, a lecture during a hike, etc. A-I-R programs also often require that artists donate some work of art to the park after their residency. For writers, this may mean allowing their writing to enter the public domain, since the park is governed by a federal agency. However, writers would generally be free to publish their work elsewhere and to adapt the work into something fundamentally new (and thus copyrightable), as with any public domain work. Such requirements would be outlined in a contract that artists would sign prior to the residency. Application requirements: Although the process will vary from park to park, generally A-I-R applications will require the following information: * An artist’s statement about your particular writing focus, your background and accomplishments * Project proposal to be undertaken in conjunction with the residency * Description of public program (workshop, reading, etc.) * Resume or curriculum vitae * Writing sample(s) * Contact information for references who know your work and can attest to your ability to work independently in this kind of residency Web sites: ** Be sure to check individual national park web sites for specific information.** National Park Service A-I-R web site National Park Arts Foundation Alliance of Artists Communities Artist-in-Residence Field Notes (for former/prospective A-I-Rs)  An arrangement at the funeral of Mr. Nguyen Ngoc Bich, March 12, 2016. An arrangement at the funeral of Mr. Nguyen Ngoc Bich, March 12, 2016. It’s an odd feeling, being a stranger to your own heritage, but that’s a feeling I’ve had most of my life. I am the daughter of an American father and a Vietnamese mother. My parents met during the war, when my father was a U.S. Army captain stationed on the base at Okinawa, Japan, where my mother had been hired to teach Vietnamese to U.S. soldiers. After a brief and passionate courtship, they married on Okinawa and moved back to the States. Unfortunately, they divorced in 1977, and my newly single father was awarded custody of my young brother and me. Thus, I grew up fully immersed in American customs, eating burgers and hot dogs, going to public school, and hanging out at the mall. It didn’t help that I was tall and white-skinned, with medium-brown hair, wholly resembling my Irish-American father. I didn’t look like my Vietnamese mother at all. Even in those times when I was with my mother, when we would cook spring rolls together or visit the Vietnamese shops at Eden Center in Falls Church, Virginia, I never felt very Vietnamese. As a child, that didn’t matter that much to me. But as I got older, I began to desire a stronger connection to my Vietnamese heritage. Without that connection, it felt like I was always standing on one leg. I sought to learn more about Vietnam and the experiences of people in the Vietnamese community. When I was in graduate school at Goucher College, studying historic preservation, I began to research and write about the section of Arlington, Virginia, that had been settled by Vietnamese immigrants and refugees after the fall of Saigon and was eventually known informally as “Little Saigon.” It didn’t take long for this work to lead me to meet Mr. Nguyen Ngoc Bich, whom I interviewed for my graduate school paper, as well as several other members of the local Vietnamese community. We sat in Mr. Bich’s basement, surrounded by his voluminous books, photos, and papers, as he told me about his many experiences in Arlington, working for the School Board and other entities in several capacities that served the local Vietnamese population. He was an author, translator, educator, community spokesperson, lobbyist, and so much more. But most of all, I remember being impressed by his warmth, intelligence, and generosity. Then, in 2004, Mr. Bich and I came together again to film a segment about Arlington’s Little Saigon for a PBS (WETA) documentary called “Arlington: Heroes, History, and Hamburgers.” Again, Mr. Bich was a sensitive, authoritative figure who offered meaningful insights about this essential time in Virginia history. His warm smile was, to me, the highlight of the segment. When I was with him, he made me feel accepted as a member of this community too. He gave me permission to stand on both legs. Some time passed, but with the 40th anniversary of the fall of Saigon in 2015, interest in commemorating Arlington’s unique Vietnamese heritage--particularly recognizing Little Saigon as the first place of refuge for Vietnamese in Virginia after the war--was growing within county government. I was honored to work with representatives from the community as well as Arlington’s historic preservation, cultural affairs, and public art departments, along with gifted students from Virginia Tech, to recognize the beginning of Vietnamese resettlement in this area. It was essential that Mr. Bich be a part of this burgeoning effort. It was a real pleasure to introduce him at a commemorative event that recognized this history through the collection of oral histories and an audio tour of the former Little Saigon, as well as a public art installation. (Mr. Bich himself recorded an oral history interview that has now been transcribed and is available to researchers at the Arlington Public Library’s Center for Local History.) This year, we were about to start work together yet again on a booklet about Arlington’s Vietnamese heritage, funded with a grant from the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Mr. Bich was to be an expert scholar on this project, and I was so pleased when he attended the kick-off meeting for this effort in January 2016. It was a shock to receive the news that Mr. Bich had passed away only about a month later. Mr. Bich’s passing is a huge loss to the Vietnamese community, as well as to the community of educators, students, historians, activists, and scholars that he has influenced both here in America as well as in Vietnam and other parts of Southeast Asia. It is also a huge loss to me personally. Mr. Bich was a generous mentor and friend who showed me what it means to be Vietnamese. Just as he helped so many people to find and hold onto their own history, Mr. Bich helped do the same for me.  Illustration by Victo Ngai for The Washington Post. Illustration by Victo Ngai for The Washington Post. When you have a child, you immediately make all the decisions for this other human being, deciding what they eat, what they wear, where they sleep, where they go, who they will play with, and so on. You are utterly, irrevocably in charge. If you happen to also be a writer, this gives you a heady power. Suddenly, this is not just a child but a font of story ideas! The Internet is littered with blogs, articles, lists, status updates, tweets, and more about what curious, adorable, touching, or infuriating things our kids are doing. I bet, in most of those cases, the parents didn't ask the kids for permission to write about them. Those rambunctious toddlers didn't sign any kind of use agreements or contracts. After all, this is mommy's life we're talking about, right? These are our children! They belong to us, so therefore we can feel free to write about them as we wish. I once thought this way too. When my son was three years old, he developed a social anxiety disorder called selective mutism (SM), wherein a child who can otherwise speak normally becomes mute in certain situations, such as school or daycare. In our case, for a while our son stopped speaking everywhere, including at home with my husband and me, and it was a very frightening and stressful time. To process what we were going through, I started a blog, now dormant, which served as both an outlet for our experiences as well as a way to connect with other families facing this same confounding condition. When I started writing, I used my son's real name and wrote about very personal things, like embarrassing play dates where he refused to cooperate, the many times I lost patience with him, and even his bathroom habits. Later, I published a personal essay about SM on the parenting site Babble, again using my son's real name. It didn't occur to me, then, that this might be an invasion of his privacy, or that if I had told him what I was doing or allowed him any agency at all, he might have objected to my writing about him. Things became clearer to me when my Babble piece was picked up on the front page of Yahoo News. For days, my very personal story went viral, garnering more than 1,000 comments and many shares. Although I received tons of support, I also got slammed by the usual contingent of trolls, as well as others who dismissed me as an overanxious mom making mountains out of molehills. What hurt the most was seeing people make judgments on my son, tossing his name around like a football. I felt like I had given birth to this child and then thrown him to the wolves. It was a hard lesson. As the years passed, the invisible umbilical that ties all mothers and children together began to stretch out. My son became more and more of his own person. I began to realize that, as much as his anxiety disorder was something I was going through and processing, it was his life I was writing about. I recognized, belatedly, that he had a right to privacy. Yes, perhaps I should have felt that way all along. But I'm glad I came to that conclusion even late in the game. I stripped his name from all my previous writings about him, and I confessed to him about all I had written. My son is now 8 years old, a talkative kid who has fully conquered selective mutism. Yet I still feel that our experience and this condition are worth writing about, so this spring I pitched an essay about him to The Washington Post. Before I did so, I asked him how he would feel if I wrote a story about him and his SM. After considering it, he agreed, but said I couldn't use his name or his photo. I totally concurred and gave my story to the Post with these restrictions, which they thankfully abided by. My article was published both in print and online, with a lovely and poignant illustration by Victo Ngai, shown here. When it was published, I asked my son if he wanted to read the story, and he said no. I didn't badger him about this. Perhaps he will tell his own version, in his own way, in the future, and I hope he does. But it's his choice. Whose life is it anyway? It's his, it's mine, and it's ours. I'll keep writing, but I'll do it out in the open.  Isaac Asimov once said that rejection slips are like "lacerations of the soul, if not quite inventions of the devil." I've been thinking about rejection a lot lately, in part because I recently gave a talk on this topic to the wonderful writers of the Capital Christian Writers group. In my talk, I referenced the remarkable tenacity of cartoonist Tom Toro, who submitted 609 cartoons to The New Yorker that were all rejected. Then, finally, his 610th cartoon struck gold, and he achieved his longtime dream of being published in The New Yorker. I've posted his very funny cartoon. I have plenty of my own rejection stories. A few years ago, I wrote a personal essay about my often-strained relationship with my mother, who is Vietnamese. I called it "The Saving Grace of Spring Rolls." I poured my heart into this story, which talked about how making my mother's beloved spring roll recipe brought us together when other things drove us apart. I believed in that story. Over the course of three years, I submitted that story to over a dozen magazines and two writing contests. It originally was about 1,800 words long. When that didn't get me anywhere, I pared it down. When that still didn't work, I reworked it, striving to find its essence. I kept sending it out, and it kept getting rejected. At some point, I took out a piece of paper and wrote "Never give up" on it five times, like this: Never give up Never give up Never give up Never give up Never give up I kept that on my desk. I kept going. I didn't give up. In November 2012, I submitted my essay to Ladies Home Journal, which had a "Story Behind the Recipe" column. By that point, my expectations were tempered. And, in predictable fashion, I heard nothing. The following February, I submitted a shorter version of my essay to the Bethesda Literary Festival writing competition in Maryland. Finally, I caught a break. The essay earned an "honorable mention" in the competition. I was thrilled that this essay that I so believed in had finally earned some validation. Then, one day in July, I had a phone call from an editor at Ladies Home Journal, a full eight months after I had submitted to them. The editor apologized for keeping me waiting and said she wanted to publish my spring roll story. Believe me, that call was so worth the wait. My piece appeared in Ladies Home Journal last May. I've come to realize that rejection is simply the universe's way of telling me that I am brave and strong, and that I am pushing myself into new and possibly uncharted territory. Rejection means that I am gaining ground, not losing it. I've come to view it as my old and helpful friend. |

Kim A. O'ConnellThoughts on writing, travel, people, and places. Categories

All

Archives

January 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed